Commentary/Writer's Blog:2012-2017

_Fishing in the Country_ Mikhail Shamegin, age 8

_Fishing in the Country_ Mikhail Shamegin, age 8

May 6, 2017

Russian Art 1989

We’re hearing a lot about Russia these days. Russia has meddled in U.S. and French elections, and they provide on-going support for the Syrian tyrant Bashar al Assad. I have another Russian story. This one’s about art – children’s art specifically. It’s a story about an event that happened around the time of the fall of the Soviet Empire.

This all began when I was on a group hike in the Ozark Mountains of northern Arkansas. The hike leader was photographer Tim Ernst. Tim was the founder of the Ozark Highlands Trail Association and author of a guidebook about the trail. During one of our breaks, Tim pulled out a letter that he had received from a Russian named Leonid who had somehow heard about Tim. Leonid, a resident of Moscow and avid wilderness hiker, wanted a pen pal in America who was also hiker.

Tim wasn’t interested, but I was. As a middle-schooler in rural West Texas, I had corresponded with school children from Singapore and Peru. I wanted more than anything as a child to see the world. And I ended up seeing quite a bit. Just how far away from home did I eventually go? In terms of miles (or kilometers), it’s tossup between Mildura, Victoria, Australia, and Zhou Zhi, Shaanxi Province, People’s Republic China. Both are really interesting places. Mildura is quite close to the world heritage Mungo National Park. Zhou Zhi is the míhóutáo 獼猴桃 capital of China - that’s kiwi fruit to English speakers. My fondest memory was hiking through a míhóutáo orchard to a tiny village where I visited the family of one of my ESL students.

So that day on the Ozarks trail, corresponding with a Russian sounded like fun to me.

Russian Art 1989

We’re hearing a lot about Russia these days. Russia has meddled in U.S. and French elections, and they provide on-going support for the Syrian tyrant Bashar al Assad. I have another Russian story. This one’s about art – children’s art specifically. It’s a story about an event that happened around the time of the fall of the Soviet Empire.

This all began when I was on a group hike in the Ozark Mountains of northern Arkansas. The hike leader was photographer Tim Ernst. Tim was the founder of the Ozark Highlands Trail Association and author of a guidebook about the trail. During one of our breaks, Tim pulled out a letter that he had received from a Russian named Leonid who had somehow heard about Tim. Leonid, a resident of Moscow and avid wilderness hiker, wanted a pen pal in America who was also hiker.

Tim wasn’t interested, but I was. As a middle-schooler in rural West Texas, I had corresponded with school children from Singapore and Peru. I wanted more than anything as a child to see the world. And I ended up seeing quite a bit. Just how far away from home did I eventually go? In terms of miles (or kilometers), it’s tossup between Mildura, Victoria, Australia, and Zhou Zhi, Shaanxi Province, People’s Republic China. Both are really interesting places. Mildura is quite close to the world heritage Mungo National Park. Zhou Zhi is the míhóutáo 獼猴桃 capital of China - that’s kiwi fruit to English speakers. My fondest memory was hiking through a míhóutáo orchard to a tiny village where I visited the family of one of my ESL students.

So that day on the Ozarks trail, corresponding with a Russian sounded like fun to me.

_At the Pet Market_Artem Ivankov, age 9

_At the Pet Market_Artem Ivankov, age 9

It turns out that Leonid lived and worked in Moscow. He had a family, a wife and three sons. His youngest was a little boy named Oleg who was seven years old. In his letters, Leonid told me about hiking trips with his club. On one trek in the higher elevations of the Caucasus Mountains, he and his hiking pals found the remains of a German soldier who had perished in the mountains during World War II.

This was 1989, and Leonid’s nation was just entering into a period momentous change. The Soviet Union had been America’s most significant Cold War rival for over forty years. This began to change when Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev began a process of democratization which led to considerable social destabilization in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe. By 1991, the Soviet Union had dissolved.

But in 1989, one of the earliest signs of all this political change was the severe shortage of key consumer products, chief among them food. Leonid admitted in one of his letters that he was concerned about his little boy Oleg who just wasn’t getting enough to eat. I had a little boy who was 10 at the time so I felt a lot of empathy as a parent.

This was 1989, and Leonid’s nation was just entering into a period momentous change. The Soviet Union had been America’s most significant Cold War rival for over forty years. This began to change when Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev began a process of democratization which led to considerable social destabilization in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe. By 1991, the Soviet Union had dissolved.

But in 1989, one of the earliest signs of all this political change was the severe shortage of key consumer products, chief among them food. Leonid admitted in one of his letters that he was concerned about his little boy Oleg who just wasn’t getting enough to eat. I had a little boy who was 10 at the time so I felt a lot of empathy as a parent.

_My Friend_Boris Salov, age 8

_My Friend_Boris Salov, age 8

I put together a care package with high protein foods: canned fish, canned chicken, beans, nuts, and peanut butter. These days mailing such a package would cost a mint. It was expensive enough in 1989, but doable.

The food was a big, big hit. Interestingly, the peanut butter was the biggest hit of all. It was a food that the Russians had never eaten. Leonid wrote in his letters that it was “the food of the gods.” Oleg loved it! Of course, I had to recommend to them PB&J sandwiches.

Leonid knew from my letters that I was artist. So he came up a proposal. He asked if he could send some pieces of artwork from the children in Oleg’s school. If I would sell the artwork and send the money to him, he would see that the families of the school children got some food relief.

I immediately connected with some fellow Quakers who were living in Moscow and teaching English at that time. They checked everything out, and we decided to go ahead.

The food was a big, big hit. Interestingly, the peanut butter was the biggest hit of all. It was a food that the Russians had never eaten. Leonid wrote in his letters that it was “the food of the gods.” Oleg loved it! Of course, I had to recommend to them PB&J sandwiches.

Leonid knew from my letters that I was artist. So he came up a proposal. He asked if he could send some pieces of artwork from the children in Oleg’s school. If I would sell the artwork and send the money to him, he would see that the families of the school children got some food relief.

I immediately connected with some fellow Quakers who were living in Moscow and teaching English at that time. They checked everything out, and we decided to go ahead.

_Self-Portrait_ Asja Rodionova, age 7

_Self-Portrait_ Asja Rodionova, age 7

Leonid sent the artwork. A local gallery in Fayetteville agreed to host the event. A local framing shop agreed to mount the artwork – all on paper – onto a heavy poster paper. We labeled each piece with a paper where art lovers could write in a bid. Friends and I organized a silent auction with a big opening reception. We connected with the wives of two visiting Russian professors at the University of Arkansas. We all met together at a friend’s house, and we created together a feast of wonderful Russian delicacies to serve at the reception.

The opening was wildly successful. The gallery was standing room only. The local tv news reporter and cameraman came and did a live report. We had music. We had food. We had art. One of the Russian women told me that it was thrilling to her to see good news about Russian when the news had been mostly bad in those days.

At the end of the evening, we announced the winners of the artwork. Eventually I ended up with five pieces - one that I had bid on and won, and the others that had been bid on but that the winners never picked up.

We raised over $1,000 that night. I sent the money on to my Quaker Friends in Moscow. They saw that the money went for food purchases for the families of children. I hope they found some peanut butter to purchase in Moscow.

~~~

More Information:

Ozark Highland Trails Association: http://ozarkhighlandstrail.com/

Photographer Tim Ernst: http://timernst.com/index.html

Dissolution of the Soviet Union: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dissolution_of_the_Soviet_Union

1989 Soviet Food Shortages: https://chnm.gmu.edu/1989/items/show/182

Mungo National Park, New South Wales, Australia: http://www.nationalparks.nsw.gov.au/visit-a-park/parks/mungo-national-park

ZhouZhi County, Shaanxi, PR China: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zhouzhi_County

Quakers in Russia: https://friendshousemoscow.org/?page_id=83

The opening was wildly successful. The gallery was standing room only. The local tv news reporter and cameraman came and did a live report. We had music. We had food. We had art. One of the Russian women told me that it was thrilling to her to see good news about Russian when the news had been mostly bad in those days.

At the end of the evening, we announced the winners of the artwork. Eventually I ended up with five pieces - one that I had bid on and won, and the others that had been bid on but that the winners never picked up.

We raised over $1,000 that night. I sent the money on to my Quaker Friends in Moscow. They saw that the money went for food purchases for the families of children. I hope they found some peanut butter to purchase in Moscow.

~~~

More Information:

Ozark Highland Trails Association: http://ozarkhighlandstrail.com/

Photographer Tim Ernst: http://timernst.com/index.html

Dissolution of the Soviet Union: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dissolution_of_the_Soviet_Union

1989 Soviet Food Shortages: https://chnm.gmu.edu/1989/items/show/182

Mungo National Park, New South Wales, Australia: http://www.nationalparks.nsw.gov.au/visit-a-park/parks/mungo-national-park

ZhouZhi County, Shaanxi, PR China: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zhouzhi_County

Quakers in Russia: https://friendshousemoscow.org/?page_id=83

November 26, 2016

The Art of Thanksgiving

Thanksgiving has long been one of my favorite American holidays. When I was living in China, one of my Chinese associates told me that she thought everyone everywhere in the world should follow the American example and a set aside a day of celebration for giving thanks.

As every school child knows, the first Thanksgiving dinner was held in 1621. Puritan colonists at Plymouth invited the local Native American tribe, the Wampanoags, to share a harvest meal. The colonists had a rough go getting established, and nearly half died in their first winter. The harvest dinner was organized to thank the Wampanoags for the tribe’s gift of food and sharing of food knowledge that made all the difference in the colonists’ survival.

However Thanksgiving as a national holiday was not established until 1863 by Abraham Lincoln in the midst of the Civil War. Here is a look at some artworks associated with this holiday.

The Art of Thanksgiving

Thanksgiving has long been one of my favorite American holidays. When I was living in China, one of my Chinese associates told me that she thought everyone everywhere in the world should follow the American example and a set aside a day of celebration for giving thanks.

As every school child knows, the first Thanksgiving dinner was held in 1621. Puritan colonists at Plymouth invited the local Native American tribe, the Wampanoags, to share a harvest meal. The colonists had a rough go getting established, and nearly half died in their first winter. The harvest dinner was organized to thank the Wampanoags for the tribe’s gift of food and sharing of food knowledge that made all the difference in the colonists’ survival.

However Thanksgiving as a national holiday was not established until 1863 by Abraham Lincoln in the midst of the Civil War. Here is a look at some artworks associated with this holiday.

Uncle Sam’s Thanksgiving

Thomas Nast was America’s first great cartoonist. In the 19th century, he regularly contributed cartoons to Harper’s magazine. Nast’s vision of Uncle Sam’s Thanksgiving (above) has been called “utopian.” This Nast woodcut first published in 1869 shows men, women, and children, whites, blacks, Chinese, and a lady with a lovely Spanish mantilla together around the Thanksgiving table. A “Universal Suffrage” sign was clearly visible.

Nast’s view was not well received in certain areas of the U.S. The Wasp, a San Francisco publication, reinterpreted Nast’s utopian vision in a much more exclusionary way. Sitting at the table are only white men, blacks are serving, and the Chinese are in the kitchen. Only one woman is visible and she’s a cook with a ladle in her hands. A few years later, the Chinese Exclusion Act was passed. Universal suffrage for blacks and women was still just an idea.

~~~

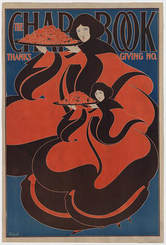

By 1895, we were in the midst of the Art Nouveau movement. Here is Will Bradley’s cover for a Thanksgiving chapbook showing a woman and her mirror image holding Thanksgiving food trays. (right)

Thomas Nast was America’s first great cartoonist. In the 19th century, he regularly contributed cartoons to Harper’s magazine. Nast’s vision of Uncle Sam’s Thanksgiving (above) has been called “utopian.” This Nast woodcut first published in 1869 shows men, women, and children, whites, blacks, Chinese, and a lady with a lovely Spanish mantilla together around the Thanksgiving table. A “Universal Suffrage” sign was clearly visible.

Nast’s view was not well received in certain areas of the U.S. The Wasp, a San Francisco publication, reinterpreted Nast’s utopian vision in a much more exclusionary way. Sitting at the table are only white men, blacks are serving, and the Chinese are in the kitchen. Only one woman is visible and she’s a cook with a ladle in her hands. A few years later, the Chinese Exclusion Act was passed. Universal suffrage for blacks and women was still just an idea.

~~~

By 1895, we were in the midst of the Art Nouveau movement. Here is Will Bradley’s cover for a Thanksgiving chapbook showing a woman and her mirror image holding Thanksgiving food trays. (right)

By the early 20th century, Thanksgiving had been romanticized. Here are two examples: Jennie Augusta Brownscombe’s, The First Thanksgiving at Plymouth (1914) and Jean Louis Gerome Ferris’s The First Thanksgiving (1915). Native Americans are prominent in each painting.

The historical reality is that not long after this first Thanksgiving, British and American colonists began an extermination campaign against the natives by giving them smallpox-infected blankets, or imprisoning them in wooden stockades then setting the stockades on fire, or just shooting, knifing, or otherwise killing them. By the time Ferris’s and Brownscombe’s paintings were created, Native American tribes had been “removed” to Oklahoma territory, then herded onto "reservations." Attempts were made to “force assimilation,” and when that didn’t work, the U.S. Army was sent to kill the warriors and their families in great battles or in massacres (aka genocide) at places like Sand Creek or Wounded Knee. Too bad those Indians didn’t build a wall when they saw the Puritans coming!

Norman Rockwell_Thanksgiving_

Norman Rockwell_Thanksgiving_

Norman Rockwell became very famous for his portrayals of American family life. This painting, Freedom from Want (left), was painted in 1943 in the midst of World War II. The focus had changed to the family. No Indians in sight.

As for me, one side of my family came with the first round of settlers at the Jamestown colony, and the other side came across the border in 1912 from the Alps in northern Italy. Our Thanksgiving table included lasagna and other Italian dishes.

I have lots to be thankful for, not least of which is the wonderful Sonoran Desert where I live. The light here is superb and it changes constantly, making for subtle and beautiful colors. Here is one of my interpretations of the desert light, Sonoran Sky Islands, Early Dawn. (oil, 30”x 30”)

(below)

As for me, one side of my family came with the first round of settlers at the Jamestown colony, and the other side came across the border in 1912 from the Alps in northern Italy. Our Thanksgiving table included lasagna and other Italian dishes.

I have lots to be thankful for, not least of which is the wonderful Sonoran Desert where I live. The light here is superb and it changes constantly, making for subtle and beautiful colors. Here is one of my interpretations of the desert light, Sonoran Sky Islands, Early Dawn. (oil, 30”x 30”)

(below)

Chavet Cave, France, 31,000 years ago

Chavet Cave, France, 31,000 years ago

November 26, 2016

Love, Work, and Money

Many of us do work that we do not love, and then we go home and do what we love in the evenings or on the weekends. Some of us do work that we love, and we get paid for doing that work. Those of us who get paid for doing what we love are usually considered lucky.

A software engineer may “love” solving software problems. The fact that he “sells” his services as a software engineer does not take aware from the fact that he loves what he is doing. We might even feel like he’s contributing a service to humanity to create a better, faster, cleverer computer for us all. How about an elementary school teacher? H/she may “love” children, and also s/he gets paid for teaching small children. I think we all agree that teaching six- year olds is real service. If you are an environmental scientist and you’re working on a project collecting data about climate change, you do so because you love the work and you think it’s important for humanity. You get paid for doing that work (and should get paid because god knows, helping to solve the climate problem is a major service to humanity). Just about any profession has this aspect to it – love of doing the work, and a willingness and desire to be paid to do it. The notion that if you do something for money, then that means you cannot love what you do is faulty thinking.

This question has arisen: if a person defines himself or herself as an artist and as a person who loves art and loves doing art, and contributes to human civilization by doing so…and also sells his/her art…does that mean his/her status as an artist is morally or ethically or existentially compromised? Is there something different about art that makes an artist compromised if s/he sells his/her work?

Love, Work, and Money

Many of us do work that we do not love, and then we go home and do what we love in the evenings or on the weekends. Some of us do work that we love, and we get paid for doing that work. Those of us who get paid for doing what we love are usually considered lucky.

A software engineer may “love” solving software problems. The fact that he “sells” his services as a software engineer does not take aware from the fact that he loves what he is doing. We might even feel like he’s contributing a service to humanity to create a better, faster, cleverer computer for us all. How about an elementary school teacher? H/she may “love” children, and also s/he gets paid for teaching small children. I think we all agree that teaching six- year olds is real service. If you are an environmental scientist and you’re working on a project collecting data about climate change, you do so because you love the work and you think it’s important for humanity. You get paid for doing that work (and should get paid because god knows, helping to solve the climate problem is a major service to humanity). Just about any profession has this aspect to it – love of doing the work, and a willingness and desire to be paid to do it. The notion that if you do something for money, then that means you cannot love what you do is faulty thinking.

This question has arisen: if a person defines himself or herself as an artist and as a person who loves art and loves doing art, and contributes to human civilization by doing so…and also sells his/her art…does that mean his/her status as an artist is morally or ethically or existentially compromised? Is there something different about art that makes an artist compromised if s/he sells his/her work?

Assyrian relief, Nimrud, 728 BC

Assyrian relief, Nimrud, 728 BC

To me, being an artist and loving what I do is in no way compromised by selling my art. It just means I (and other artists, too) will have money to pay for paints and canvases, and the electric bill, and we’ll have something to eat. It’s the same with writers. Writers often sell their books, their short-stories, and their poems – or they hope to sell and try to sell. Unless writers are independently wealthy, they sell work so they can have enough money to keep going and write more. I would never criticize, for example, a novelist for attempting to sell his/her novel. And I do not see a writer compromised by attempting to sell his/her writings.

I know someone who has loved animals all her life. She loves animals so much that she became a veterinarian so she could take care of her beloved animals. She saw no problem with making money doing what she loved. She loves animals, especially horses, and she loves taking care of them. She made her living as a vet for many years. She is also an artist, and has been an artist for most of her adult life. She loves animals and she loves art. So she creates sculptures of horses and other animals. She sells her sculptures. She actively markets her artwork. She exhibits in galleries and at festivals and other events in the hopes of selling her work. Her home near Tucson is a wonderful place to visit. Her acreage has an outdoor sculpture garden with a trail that passes through a host of animal sculptures. Many are for sale. She also gives away some of her artwork to auctions to raise money for wildlife conservation.

I know someone who has loved animals all her life. She loves animals so much that she became a veterinarian so she could take care of her beloved animals. She saw no problem with making money doing what she loved. She loves animals, especially horses, and she loves taking care of them. She made her living as a vet for many years. She is also an artist, and has been an artist for most of her adult life. She loves animals and she loves art. So she creates sculptures of horses and other animals. She sells her sculptures. She actively markets her artwork. She exhibits in galleries and at festivals and other events in the hopes of selling her work. Her home near Tucson is a wonderful place to visit. Her acreage has an outdoor sculpture garden with a trail that passes through a host of animal sculptures. Many are for sale. She also gives away some of her artwork to auctions to raise money for wildlife conservation.

Prayer Flags

Prayer Flags

November 15, 2016

Love Trumps Hate Prayer Flags

I have been very distressed at the process and outcome of this year’s presidential election….more than any election I can remember in my lifetime (and I’ve lived through quite a few!). I blame us ALL – we Americans from the political Left to the political Right, from the so-called “elite” big-city know-it-alls to the folks living in “fly over” America who seem to want to return to the 1950s. Seriously…how did we get to the point that we had to choose between “bad” and “catastrophic” and then catastrophic prevails? Good grief! In recent days, I’ve been thinking about how to respond. From the historical records, we know that storytelling and artwork are two ways that can be very effective at processing trauma and figuring out what to do next.

I plan to write about the election (more on that later), but for now, here is one artist’s response. I share with you a project being organized by Portland, OR, artist Shu-Ju Wang. Some of you had the pleasure of taking Shu-Ju’s Gocco printing workshop here in Tucson through PaperWorks a few years ago. Shu-Ju’s project is called Love Trumps Hate Prayer Flags. There will be a maximum of 60 artists, and there’s not much room left. If you don’t get into her project, then a similar project could be done here!

Shu-Ju explains in her own words: - I am initiating a community participation project to print prayer flags in time to fly on Inauguration Day, Jan 20, 2017. Details -- you supply 1 yard of cotton fabric and a hand-written "Love Trumps Hate" text (decorations optional), and I will supply all the inks and silkscreens (Print Gocco). I must receive your text & fabric by Dec 10 so the project can be completed in time. To participate, email me (now closed). We will print 4"x6" rectangles of Love Trumps Hate flags and everyone will swap and get a collection. You will take your collection and string/sew/staple/however them on to a string, and put them up in time for inauguration. I want a minimum of 20 participants and a maximum of 60. I'll organize a printing party for Portland participants; if you're not in Portland, I can print yours for you. If you're inspired by this, please start your own community project!

Love Trumps Hate Prayer Flags

I have been very distressed at the process and outcome of this year’s presidential election….more than any election I can remember in my lifetime (and I’ve lived through quite a few!). I blame us ALL – we Americans from the political Left to the political Right, from the so-called “elite” big-city know-it-alls to the folks living in “fly over” America who seem to want to return to the 1950s. Seriously…how did we get to the point that we had to choose between “bad” and “catastrophic” and then catastrophic prevails? Good grief! In recent days, I’ve been thinking about how to respond. From the historical records, we know that storytelling and artwork are two ways that can be very effective at processing trauma and figuring out what to do next.

I plan to write about the election (more on that later), but for now, here is one artist’s response. I share with you a project being organized by Portland, OR, artist Shu-Ju Wang. Some of you had the pleasure of taking Shu-Ju’s Gocco printing workshop here in Tucson through PaperWorks a few years ago. Shu-Ju’s project is called Love Trumps Hate Prayer Flags. There will be a maximum of 60 artists, and there’s not much room left. If you don’t get into her project, then a similar project could be done here!

Shu-Ju explains in her own words: - I am initiating a community participation project to print prayer flags in time to fly on Inauguration Day, Jan 20, 2017. Details -- you supply 1 yard of cotton fabric and a hand-written "Love Trumps Hate" text (decorations optional), and I will supply all the inks and silkscreens (Print Gocco). I must receive your text & fabric by Dec 10 so the project can be completed in time. To participate, email me (now closed). We will print 4"x6" rectangles of Love Trumps Hate flags and everyone will swap and get a collection. You will take your collection and string/sew/staple/however them on to a string, and put them up in time for inauguration. I want a minimum of 20 participants and a maximum of 60. I'll organize a printing party for Portland participants; if you're not in Portland, I can print yours for you. If you're inspired by this, please start your own community project!

CJShane_Mala with Daoist amulet_

CJShane_Mala with Daoist amulet_

February 10, 2016

Malas

Like thousands of other Tucsonans, I went to the Gem and Mineral Show this past week. I was in search of something specific – amulets to include with the meditation malas I’ve begun making again after a long hiatus. I was lucky and found amulets from several traditions at the Gem show.

What is a mala? Wikipedia defines “mala” as “a bead or a set of beads commonly used by Hindus and Buddhists for keeping count while reciting, chanting, or mentally repeating a mantra or the name or names of a deity.”

This image (left) shows a mala I made using Chinese landscape jasper beads and a Daoist amulet showing Tai Shang Lao Jun, one of the three Pure Ones or Divine Teachers in Daoism (Taoism). These teachers are regarded as pure manifestations of the Dao (The Way). [click on all images to enlarge]

Malas

Like thousands of other Tucsonans, I went to the Gem and Mineral Show this past week. I was in search of something specific – amulets to include with the meditation malas I’ve begun making again after a long hiatus. I was lucky and found amulets from several traditions at the Gem show.

What is a mala? Wikipedia defines “mala” as “a bead or a set of beads commonly used by Hindus and Buddhists for keeping count while reciting, chanting, or mentally repeating a mantra or the name or names of a deity.”

This image (left) shows a mala I made using Chinese landscape jasper beads and a Daoist amulet showing Tai Shang Lao Jun, one of the three Pure Ones or Divine Teachers in Daoism (Taoism). These teachers are regarded as pure manifestations of the Dao (The Way). [click on all images to enlarge]

CJShane_Mala in progress, hamsa amulet_

CJShane_Mala in progress, hamsa amulet_

We humans have used prayer beads and malas to help us in our meditations since the beginning of time. Now in the modern era, many who are not believers in any particular religion are still quite devoted to meditation because of meditation’s many documented health benefits, both physical and mental.

We also have used the amulets and talismans associated with malas and prayers beads as a kind of ornamentation. Many westerners wear malas as necklaces – knowing or not knowing the spiritual quality of the “necklace,” but benefiting all the same.

This image (right) shows one of my malas in progress. This one is created from zebra jasper bead, a Hamsa amulet, and knotted waxed linen thread. I usually use semi-precious stone beads: jasper, turquoise, jade, etc.

amulets from world traditions

amulets from world traditions

In this image (left), let's take a tour of amulets The top row has Daoist and Buddhist amulets. In the second row on the left, we find more Buddhist amulets, this time featuring Guan Yin, the Buddhist bodhisattva of compassion, the goddess of mercy.

In the center of the second row are two versions of “Om” which is the sacred sound and Sanskrit symbol in all Indian religions: Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism. The sound is often used as a mantra during meditation. On the far right is a smooth river stone. I incorporate river stones into malas for those of us who don’t identify with any particular religion but who connect more to the unity of all life on our Mother Earth.

In the bottom row on the left is the small, gold ankh which is an Egyptian symbol for life or the breath of life. Next are the hands known as Hamsas which come from the Jewish and Muslim traditions. These hands symbolize the Hand of God. A hamsa is a protective sign that represents happiness, good luck and good health. On the far right are the Christian symbols: the Cross – both western and Ethiopian Coptic; and the fish or the Greek ichthys (ἰχθύς) symbol which represents Jesus, the Fisher of Men.

In the center of the second row are two versions of “Om” which is the sacred sound and Sanskrit symbol in all Indian religions: Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism. The sound is often used as a mantra during meditation. On the far right is a smooth river stone. I incorporate river stones into malas for those of us who don’t identify with any particular religion but who connect more to the unity of all life on our Mother Earth.

In the bottom row on the left is the small, gold ankh which is an Egyptian symbol for life or the breath of life. Next are the hands known as Hamsas which come from the Jewish and Muslim traditions. These hands symbolize the Hand of God. A hamsa is a protective sign that represents happiness, good luck and good health. On the far right are the Christian symbols: the Cross – both western and Ethiopian Coptic; and the fish or the Greek ichthys (ἰχθύς) symbol which represents Jesus, the Fisher of Men.

December 20, 2015

Shopping For School Clothes

My family and I, my parents and my younger sister, lived in a small town on the high plains prairie of the Texas Panhandle in the far north not far from Kansas. The land was old Comanche territory where the wind blew all the time – and still blows all the time. This little town had one traffic light. My classmates’ parents either worked in the oil and gas industry or they were farmers or ranchers. The farmers grew sorghum and winter wheat. The ranchers ran Hereford cattle. About 2,500 people lived in the town, and all of them were white.

My family drove to the nearest big city, Amarillo, to do major shopping. We also ate out at a cafeteria which was noteworthy for having an organist play while we ate. I always chose meatloaf. Major shopping trips to Amarillo were usually devoted to buying school clothes. We always went to a department store called Fedway. I’m almost certain that my parents had an account there to charge and pay off purchases. Fedway was an exciting place for a child in elementary school. It had multiple stories and large selections of consumer goods on every floor. Fedway seemed very sophisticated.

Once when I was in maybe fourth grade (around 1956 or 1957), I had to go to the bathroom. My mother was helping my sister try on clothes, and my dad was off somewhere – wherever men go to avoid shopping. My mother told me to go on by myself and find the bathroom. You could do that in those days – let a young child go off alone – because crimes against children were either fewer or better hidden.

The first bathroom had a sign on the door that said, “Colored Women.” I didn’t know what “colored” meant when it appeared before the word “women,” but I figured it was okay for me to go in because I fit in the “women” category. So I went in. The bathroom was small with only one stall and toilet. The walls were a dark gray and chipped as if it hadn’t been painted in a long time. There was only one light in the room, a bare lightbulb in a fixture near the ceiling.

Just as I finished and was washing my hands, a tall black woman came in with her small daughter. Maybe the little girl was four or five. It was clear that the child was afraid of me. She stared at me intently and hid behind her mother. I remember feeling vaguely uncomfortable, as if I’d done something I shouldn’t have done. I was curious, too. I knew about black people. I had seen them on the television, but I don’t ever remember encountering a black person in reality. I returned to my mother and sister.

Not long after, my sister had to go to the bathroom. So all three of us went to the women’s bathroom, but not the same one that I’d visited earlier. We went to a door labeled “Women’s Restroom.” This restroom was large with multiple stalls and toilets. The room was well-lit with many light fixtures. The walls were gleaming ceramic tiles of pink and white. There were several sinks to wash your hands. The restroom looked new and fresh and inviting, and quite unlike the one I had visited earlier on my own.

There was news even then about the struggle that blacks were going through to attain full human rights in this country. Of course, that struggle took place far away from where I lived, and it had nothing to do with me. I never thought about black people. All that changed after visiting the two bathrooms.

I got it. In that moment when I entered the pink bathroom, everything became clear. One big whole of awareness fell upon me. I understood for the first time what racism was. I understood that all the adults I knew were complicit in something really wrong. I could see that there was no rational reason for blacks to be shuffled off to dark, dank, gray-walled, small toilets and not ever allowed in the well-lit pink tile bathrooms. Clearly I was looking at something very unfair. This was just one of many times that I would come to question what I had been taught by the adults around me.

I never talked to my parents about this. But I never forgot. Some years later Martin Luther King, Jr., was awarded a Nobel peace prize. My dad said that he disapproved of this because “King has done more to upset the peace than anyone I know.” To myself I said, I know why King has done what he’s done. He’s trying to make it possible for that little black girl to go into the big pink bathroom.

Later I would read that the first black clerk at Fedway was Iris Elaine Sanders Lawrence. She was born in Amarillo and grew up there. She went off to college and earned her bachelor’s degree from St. Augustine’s College in Raleigh, N.C. On a trip home from college in 1961, she and some friends were denied entrance into the Paramount movie theater in Amarillo. In response, she and her classmates started a protest of this segregation outside in the street. Lawrence and the other students were jailed for disturbing the peace.

“Even though I was in jail, I wasn’t afraid,” she said. “Everything started back then in the churches, where our parents were the leaders in the community, so my dad, John Sanders, and my pastor, Rev. L.B. George, told us before we even left for the movies, ‘Don’t be afraid, because we are backing you.’” (from Amarillo Globe News)

Lawrence eventually worked as an English teacher in the Amarillo school district. She was the first black woman to serve in many significant positions, including the first elected as Potter County Commissioner. She also was delegate to the Democratic National Convention in 1984 and 2000. From 2000 to 2004, she was the Texas Democratic National Committeewoman, and she was a member of the governing board of the Texas Organization of Black County Commissioners. She is retired now and lives in Amarillo today. Iris Elaine Sanders Lawrence can go into the pink bathroom in Fedway any time she wants.

Shopping For School Clothes

My family and I, my parents and my younger sister, lived in a small town on the high plains prairie of the Texas Panhandle in the far north not far from Kansas. The land was old Comanche territory where the wind blew all the time – and still blows all the time. This little town had one traffic light. My classmates’ parents either worked in the oil and gas industry or they were farmers or ranchers. The farmers grew sorghum and winter wheat. The ranchers ran Hereford cattle. About 2,500 people lived in the town, and all of them were white.

My family drove to the nearest big city, Amarillo, to do major shopping. We also ate out at a cafeteria which was noteworthy for having an organist play while we ate. I always chose meatloaf. Major shopping trips to Amarillo were usually devoted to buying school clothes. We always went to a department store called Fedway. I’m almost certain that my parents had an account there to charge and pay off purchases. Fedway was an exciting place for a child in elementary school. It had multiple stories and large selections of consumer goods on every floor. Fedway seemed very sophisticated.

Once when I was in maybe fourth grade (around 1956 or 1957), I had to go to the bathroom. My mother was helping my sister try on clothes, and my dad was off somewhere – wherever men go to avoid shopping. My mother told me to go on by myself and find the bathroom. You could do that in those days – let a young child go off alone – because crimes against children were either fewer or better hidden.

The first bathroom had a sign on the door that said, “Colored Women.” I didn’t know what “colored” meant when it appeared before the word “women,” but I figured it was okay for me to go in because I fit in the “women” category. So I went in. The bathroom was small with only one stall and toilet. The walls were a dark gray and chipped as if it hadn’t been painted in a long time. There was only one light in the room, a bare lightbulb in a fixture near the ceiling.

Just as I finished and was washing my hands, a tall black woman came in with her small daughter. Maybe the little girl was four or five. It was clear that the child was afraid of me. She stared at me intently and hid behind her mother. I remember feeling vaguely uncomfortable, as if I’d done something I shouldn’t have done. I was curious, too. I knew about black people. I had seen them on the television, but I don’t ever remember encountering a black person in reality. I returned to my mother and sister.

Not long after, my sister had to go to the bathroom. So all three of us went to the women’s bathroom, but not the same one that I’d visited earlier. We went to a door labeled “Women’s Restroom.” This restroom was large with multiple stalls and toilets. The room was well-lit with many light fixtures. The walls were gleaming ceramic tiles of pink and white. There were several sinks to wash your hands. The restroom looked new and fresh and inviting, and quite unlike the one I had visited earlier on my own.

There was news even then about the struggle that blacks were going through to attain full human rights in this country. Of course, that struggle took place far away from where I lived, and it had nothing to do with me. I never thought about black people. All that changed after visiting the two bathrooms.

I got it. In that moment when I entered the pink bathroom, everything became clear. One big whole of awareness fell upon me. I understood for the first time what racism was. I understood that all the adults I knew were complicit in something really wrong. I could see that there was no rational reason for blacks to be shuffled off to dark, dank, gray-walled, small toilets and not ever allowed in the well-lit pink tile bathrooms. Clearly I was looking at something very unfair. This was just one of many times that I would come to question what I had been taught by the adults around me.

I never talked to my parents about this. But I never forgot. Some years later Martin Luther King, Jr., was awarded a Nobel peace prize. My dad said that he disapproved of this because “King has done more to upset the peace than anyone I know.” To myself I said, I know why King has done what he’s done. He’s trying to make it possible for that little black girl to go into the big pink bathroom.

Later I would read that the first black clerk at Fedway was Iris Elaine Sanders Lawrence. She was born in Amarillo and grew up there. She went off to college and earned her bachelor’s degree from St. Augustine’s College in Raleigh, N.C. On a trip home from college in 1961, she and some friends were denied entrance into the Paramount movie theater in Amarillo. In response, she and her classmates started a protest of this segregation outside in the street. Lawrence and the other students were jailed for disturbing the peace.

“Even though I was in jail, I wasn’t afraid,” she said. “Everything started back then in the churches, where our parents were the leaders in the community, so my dad, John Sanders, and my pastor, Rev. L.B. George, told us before we even left for the movies, ‘Don’t be afraid, because we are backing you.’” (from Amarillo Globe News)

Lawrence eventually worked as an English teacher in the Amarillo school district. She was the first black woman to serve in many significant positions, including the first elected as Potter County Commissioner. She also was delegate to the Democratic National Convention in 1984 and 2000. From 2000 to 2004, she was the Texas Democratic National Committeewoman, and she was a member of the governing board of the Texas Organization of Black County Commissioners. She is retired now and lives in Amarillo today. Iris Elaine Sanders Lawrence can go into the pink bathroom in Fedway any time she wants.

Photo: Larry Mayer

Photo: Larry Mayer

November 18, 2012

Avoidance

Tucson photographer Larry Mayer recently posted on Google + a fascinating commentary on the neurobiology of approach and avoidance in humans. He illustrated this with one of his own photographs. He also points out the value of street photography to document this avoidance phenomenon as it relates to being solicited for money on the street. Note how carefully I phrase this. To refer to those persons asking for money as “beggars” or “panhandlers” or “a needy person” or some other term carries with it a point of view on how we perceive the request for money – whether we feel approach or avoidance, in other words.

His photo shows a man steadfastly avoiding an elderly, poorly-dressed woman begging for money. Larry says, “I watched tourist after tourist, without exception, avoid the woman with the outstretched cup. The behavior is called “Avoidance” and is linked with fundamentals of the brain and associated with a critical balance between avoidance and approach.” You can see Larry Mayer’s photo and read his commentary at https://plus.google.com/u/0/118019328633110210449/posts/f1G2CR71bui

Given that we humans hope for a healthy balance between avoidance and approach, Larry is quite correct to point to the hard-wiring in our brains and its effect on how we react to these events. Too much “avoidance” wiring in the brain can lead to a dysfunctional relationship to the external world and to other humans. And it follows that too much “approach” in the brain will surely lead to perpetually empty pockets.

What interests me more about this is not so much the extremes of hard-wiring, but the folks with more balance between approach and avoidance in our brains. Why do we “balanced” individuals choose avoidance sometimes and approach at others? I suspect cultural expectations have a big role in that. Questions come to mind. Is it easier for an elderly person, an adult, or a child to elicit charity? Easier for a male or a female? A person accompanied by a child or alone? A person is clearly disabled versus one who is not? What are the cultural cues that we receive that lead us to either approach or avoid these folks? And after we make a “contribution,” how do we feel about ourselves?

I’ve spent quite a bit of time in China. Larry’s photo brought to mind several encounters I had with individuals seeking charity in that country. I want to make clear first, though, that I’ve encountered beggars in every country I’ve visited including the U.S., including in Tucson, including the Walmart parking lot at Grant and Alvernon. So China is certainly not unique in having beggars. That said, observing this approach-avoidance behavior in China brought up in my mind many questions about my own culture.

I am often approached in the U.S. by individuals with a hard-luck story. That hasn’t happened so much to me in China. There, I am more likely to be asked to purchase something of little value. I was approached by a very elderly woman on the streets of Yangshuo wanting to sell me little bracelets made of tacky plastic beads and elastic thread. I bought two for the sum of 5 yuan each, (a total of $1.60 US) when I’m sure they were worth much less. I made no attempt to negotiate a lower price as is common in China. The elderly woman smiled the whole time and touched my cheek in gratitude when I handed over the money. I came away from this interaction feeling that she really and truly was desperate, and that I had made it possible for her to eat that day.

On the other hand, I was approached recently by a man at a quick-stop gas station in Tucson. His story was that he had run out of gas, needed $8 to get enough gas to get home to the far northern suburbs. When I gave him $1, he was visibly irritated and chidingly reminded me of how much he really needed. He kept the dollar and stomped off in annoyance.

Needless to say, I felt like I had done a good deed with the old Chinese woman in Yangshuo and very likely got ripped off by the American who needed gas money. The old woman had no “story” because neither of us spoke each other’s language. What were her cues that made her seem more authentic and truly needy compared to a man who explained in a plausible way why he needed a handout? If the man asking for gas money had just taken the dollar without complaining, how much better would I have felt? Would I have believed him then?

Was it intuition that led me to purchase items from the old woman consciously knowing that my purchase was really charity? What is “intuition” anyway? Is it some kind of hard-wiring in my brain that makes it possible to pick up cues and information not normally available to our conscious mind? Was it intuition that caused me to doubt the man’s story? Did the old woman have more “dignity” because she was selling something rather than just asking for a handout? There are some who will think this even though the product being sold was next to worthless. My friend Marianne thinks that beggars who simply ask for a handout are working at the performance of begging, and that they deserve to be paid for their work. Most Americans don’t feel that way, and probably have a preference for buying some little trinket over paying for a “begging performance.” Was my real problem with the man simply that his performance was inferior, and his story worth only $1, not $8?

The worse cases of street beggars that I have ever seen involve the exploitation of children. I watched a constant stream of adults walk around and sometimes step over a small girl, maybe 6 or 7 years old, on the street in Xi’an. She was dirty and dressed in ragged clothing sitting on the sidewalk with her hand out muttering her plea for money. I have been told many times by the Chinese that these kids, usually little girls, are controlled by exploitative adults who send them out to the street, collect the take at the end of the day, and give the child just enough to eat and a place to sleep to keep going the next day…and the next…and the next. Many Chinese have told me that giving money only helps the exploiter and that it’s “the government’s job” to end the exploitation. But I’m looking at a little girl who is hungry and has been on the street all day. Okay. So I gave her some money anyway. Was that the right thing to do?

I know for sure I don’t want to be a person who can comfortably say to herself, “IT TAKES A WHILE BEFORE YOU CAN STEP OVER INERT BODIES AND GO AHEAD WITH WHAT YOU WERE TRYING TO DO.” This quote is from artist Jenny Holzer and her Living Series sculptures (1989).

We don’t see child beggars so much in the U.S. because we’ve managed to manipulate things so that we don’t have to confront extreme poverty in children. Consequently we don’t have to step over their little bodies on the street. We don’t have to feel things we don’t want to feel. And a significant percentage of us find it difficult to say (for different reasons) that “it’s the government’s job” to solve the problem of child poverty.

It is common in the U.S. for poverty-stricken children to come to school hungry each day. Hunger in students is a persistent problem for school teachers. Teachers have their own way of dealing with it because no one else will. The saddest story I’ve heard came from teacher who found a six-year old stuffing mashed potatoes from his free school lunch into his pockets to take home to his four-year-old sister. The boy said his sister would have nothing to eat that day other than what he managed to save from lunch. This happened in Tucson.

Does it take an artist with his street photos or with her pithy truisms to reveal what we are really doing when we go into “avoidance” mode? Perhaps in this case anyway, art is a way of pointing at the truth.

Avoidance

Tucson photographer Larry Mayer recently posted on Google + a fascinating commentary on the neurobiology of approach and avoidance in humans. He illustrated this with one of his own photographs. He also points out the value of street photography to document this avoidance phenomenon as it relates to being solicited for money on the street. Note how carefully I phrase this. To refer to those persons asking for money as “beggars” or “panhandlers” or “a needy person” or some other term carries with it a point of view on how we perceive the request for money – whether we feel approach or avoidance, in other words.

His photo shows a man steadfastly avoiding an elderly, poorly-dressed woman begging for money. Larry says, “I watched tourist after tourist, without exception, avoid the woman with the outstretched cup. The behavior is called “Avoidance” and is linked with fundamentals of the brain and associated with a critical balance between avoidance and approach.” You can see Larry Mayer’s photo and read his commentary at https://plus.google.com/u/0/118019328633110210449/posts/f1G2CR71bui

Given that we humans hope for a healthy balance between avoidance and approach, Larry is quite correct to point to the hard-wiring in our brains and its effect on how we react to these events. Too much “avoidance” wiring in the brain can lead to a dysfunctional relationship to the external world and to other humans. And it follows that too much “approach” in the brain will surely lead to perpetually empty pockets.

What interests me more about this is not so much the extremes of hard-wiring, but the folks with more balance between approach and avoidance in our brains. Why do we “balanced” individuals choose avoidance sometimes and approach at others? I suspect cultural expectations have a big role in that. Questions come to mind. Is it easier for an elderly person, an adult, or a child to elicit charity? Easier for a male or a female? A person accompanied by a child or alone? A person is clearly disabled versus one who is not? What are the cultural cues that we receive that lead us to either approach or avoid these folks? And after we make a “contribution,” how do we feel about ourselves?

I’ve spent quite a bit of time in China. Larry’s photo brought to mind several encounters I had with individuals seeking charity in that country. I want to make clear first, though, that I’ve encountered beggars in every country I’ve visited including the U.S., including in Tucson, including the Walmart parking lot at Grant and Alvernon. So China is certainly not unique in having beggars. That said, observing this approach-avoidance behavior in China brought up in my mind many questions about my own culture.

I am often approached in the U.S. by individuals with a hard-luck story. That hasn’t happened so much to me in China. There, I am more likely to be asked to purchase something of little value. I was approached by a very elderly woman on the streets of Yangshuo wanting to sell me little bracelets made of tacky plastic beads and elastic thread. I bought two for the sum of 5 yuan each, (a total of $1.60 US) when I’m sure they were worth much less. I made no attempt to negotiate a lower price as is common in China. The elderly woman smiled the whole time and touched my cheek in gratitude when I handed over the money. I came away from this interaction feeling that she really and truly was desperate, and that I had made it possible for her to eat that day.

On the other hand, I was approached recently by a man at a quick-stop gas station in Tucson. His story was that he had run out of gas, needed $8 to get enough gas to get home to the far northern suburbs. When I gave him $1, he was visibly irritated and chidingly reminded me of how much he really needed. He kept the dollar and stomped off in annoyance.

Needless to say, I felt like I had done a good deed with the old Chinese woman in Yangshuo and very likely got ripped off by the American who needed gas money. The old woman had no “story” because neither of us spoke each other’s language. What were her cues that made her seem more authentic and truly needy compared to a man who explained in a plausible way why he needed a handout? If the man asking for gas money had just taken the dollar without complaining, how much better would I have felt? Would I have believed him then?

Was it intuition that led me to purchase items from the old woman consciously knowing that my purchase was really charity? What is “intuition” anyway? Is it some kind of hard-wiring in my brain that makes it possible to pick up cues and information not normally available to our conscious mind? Was it intuition that caused me to doubt the man’s story? Did the old woman have more “dignity” because she was selling something rather than just asking for a handout? There are some who will think this even though the product being sold was next to worthless. My friend Marianne thinks that beggars who simply ask for a handout are working at the performance of begging, and that they deserve to be paid for their work. Most Americans don’t feel that way, and probably have a preference for buying some little trinket over paying for a “begging performance.” Was my real problem with the man simply that his performance was inferior, and his story worth only $1, not $8?

The worse cases of street beggars that I have ever seen involve the exploitation of children. I watched a constant stream of adults walk around and sometimes step over a small girl, maybe 6 or 7 years old, on the street in Xi’an. She was dirty and dressed in ragged clothing sitting on the sidewalk with her hand out muttering her plea for money. I have been told many times by the Chinese that these kids, usually little girls, are controlled by exploitative adults who send them out to the street, collect the take at the end of the day, and give the child just enough to eat and a place to sleep to keep going the next day…and the next…and the next. Many Chinese have told me that giving money only helps the exploiter and that it’s “the government’s job” to end the exploitation. But I’m looking at a little girl who is hungry and has been on the street all day. Okay. So I gave her some money anyway. Was that the right thing to do?

I know for sure I don’t want to be a person who can comfortably say to herself, “IT TAKES A WHILE BEFORE YOU CAN STEP OVER INERT BODIES AND GO AHEAD WITH WHAT YOU WERE TRYING TO DO.” This quote is from artist Jenny Holzer and her Living Series sculptures (1989).

We don’t see child beggars so much in the U.S. because we’ve managed to manipulate things so that we don’t have to confront extreme poverty in children. Consequently we don’t have to step over their little bodies on the street. We don’t have to feel things we don’t want to feel. And a significant percentage of us find it difficult to say (for different reasons) that “it’s the government’s job” to solve the problem of child poverty.

It is common in the U.S. for poverty-stricken children to come to school hungry each day. Hunger in students is a persistent problem for school teachers. Teachers have their own way of dealing with it because no one else will. The saddest story I’ve heard came from teacher who found a six-year old stuffing mashed potatoes from his free school lunch into his pockets to take home to his four-year-old sister. The boy said his sister would have nothing to eat that day other than what he managed to save from lunch. This happened in Tucson.

Does it take an artist with his street photos or with her pithy truisms to reveal what we are really doing when we go into “avoidance” mode? Perhaps in this case anyway, art is a way of pointing at the truth.